Kowloon Walled City

九龍城寨 Aerial view of the Kowloon Walled City, 1989

Aerial view of the Kowloon Walled City, 1989Photo Credit: Ian Lambot

Coordinates: 22°19′56″N 114°11′25″E

| Country/City: |  Hong Kong Hong Kong |

|

| District:: | Kowloon City District | |

| Area: | Kowloon City | |

| Settled: | c. 1945 | |

| Demolished: | 1994 | |

| Total Area: | 2.6 ha (6.4 acres) | |

| Population (1990) | ||

| Total: | 50,000 | |

| Density: | 1,255,000/km2 (3,250,000/sq mi) | |

Audio from Shenmue II - "Ren's Hideout"

The Walled City of Kowloon

"Sin City", "The City of Darkness", "The City of Anarchy"

Kowloon Walled City was an ungoverned, densely populated settlement located in Kowloon City, Hong Kong, considered to have been the densest settlement on Earth.

Originally a Chinese outpost set up to manage the salt trade during the Song Dynasty (960AD-1279), it was later turned into a Military outpost with an added coastal fort in the 1800s. When China lost to the British in the first Opium War, Hong Kong was officially handed over in 1842 - though the Kowloon site was an exception, with the British allowing the Chinese to stay at the site as long as they did not politically interfere. China would reclaim ownership of the site in 1947, but its separation from the mainland meant they did little to enforce laws. It became a haven for refugees fleeing the Chinese Civil War post-1945, with 2,000 squatters occupying the Walled City in 1947. After a failed attempt to drive them out in 1948, the British adopted a 'hands-off' policy in most matters concerning the Walled City.

As the City's population grew, the residents kept building new modular structures on top of older ones, all without help from architects or engineers and without having to adhere to building codes or sanitation regulations, becoming a confined mass of roughly 300 illegally-constructed, haphazardly-built residential towers by the end of the 1960s. The buildings were packed together so tightly that only 5% of the City ever saw direct sunlight. The Walled City became a world unto its own, an interconnected maze of passageways and staircases topped with television antennae and washing lines.

The lack of government involvement also allowed the Walled City to become a hotbed of criminal activity. Triads virtually took control of the Walled City, free to run brothels, casinos and opium dens. Police did not patrol the Walled City, and in rare cases of serious crimes (such as murder) would only go in with big squads of 30 or so. Despite this lack of law enforcement, however, most residents were not involved in any crimes and lived peacefully within the City's walls.

It reached its maximum size by the late 1970s and early 1980s, with a height restriction of 13 to 14 storeys being imposed on the City to account for the flight path of planes heading toward Kai Tak Airport, one of the few regulations the City would ever follow.

Reportedly, over 40,000 people lived within the Walled City's 2.6-hectare (6.4-acre) space.

The Walled City was demolished on April 1994, with Kowloon Walled City Park opening in its place in December 1995.

Originally a Chinese outpost set up to manage the salt trade during the Song Dynasty (960AD-1279), it was later turned into a Military outpost with an added coastal fort in the 1800s. When China lost to the British in the first Opium War, Hong Kong was officially handed over in 1842 - though the Kowloon site was an exception, with the British allowing the Chinese to stay at the site as long as they did not politically interfere. China would reclaim ownership of the site in 1947, but its separation from the mainland meant they did little to enforce laws. It became a haven for refugees fleeing the Chinese Civil War post-1945, with 2,000 squatters occupying the Walled City in 1947. After a failed attempt to drive them out in 1948, the British adopted a 'hands-off' policy in most matters concerning the Walled City.

As the City's population grew, the residents kept building new modular structures on top of older ones, all without help from architects or engineers and without having to adhere to building codes or sanitation regulations, becoming a confined mass of roughly 300 illegally-constructed, haphazardly-built residential towers by the end of the 1960s. The buildings were packed together so tightly that only 5% of the City ever saw direct sunlight. The Walled City became a world unto its own, an interconnected maze of passageways and staircases topped with television antennae and washing lines.

The lack of government involvement also allowed the Walled City to become a hotbed of criminal activity. Triads virtually took control of the Walled City, free to run brothels, casinos and opium dens. Police did not patrol the Walled City, and in rare cases of serious crimes (such as murder) would only go in with big squads of 30 or so. Despite this lack of law enforcement, however, most residents were not involved in any crimes and lived peacefully within the City's walls.

It reached its maximum size by the late 1970s and early 1980s, with a height restriction of 13 to 14 storeys being imposed on the City to account for the flight path of planes heading toward Kai Tak Airport, one of the few regulations the City would ever follow.

Reportedly, over 40,000 people lived within the Walled City's 2.6-hectare (6.4-acre) space.

The Walled City was demolished on April 1994, with Kowloon Walled City Park opening in its place in December 1995.

Contents

History

Information sourced from Wikipedia.

In 1842, during Qing Emperor Daoguang's reign, Hong Kong Island was ceded to Britain by the Treaty of Nanjing. As a result, the Qing authorities felt it necessary to improve the fort in order to rule the area and check further British influence. The improvements, including the formidable defensive wall, were completed in 1847. The Walled City was captured by rebels during the Taiping Rebellion in 1854 before being retaken a few weeks later. The present Walled City's "Dapeng Association House" forms the remnants of what was previously Lai Enjue's garrison.

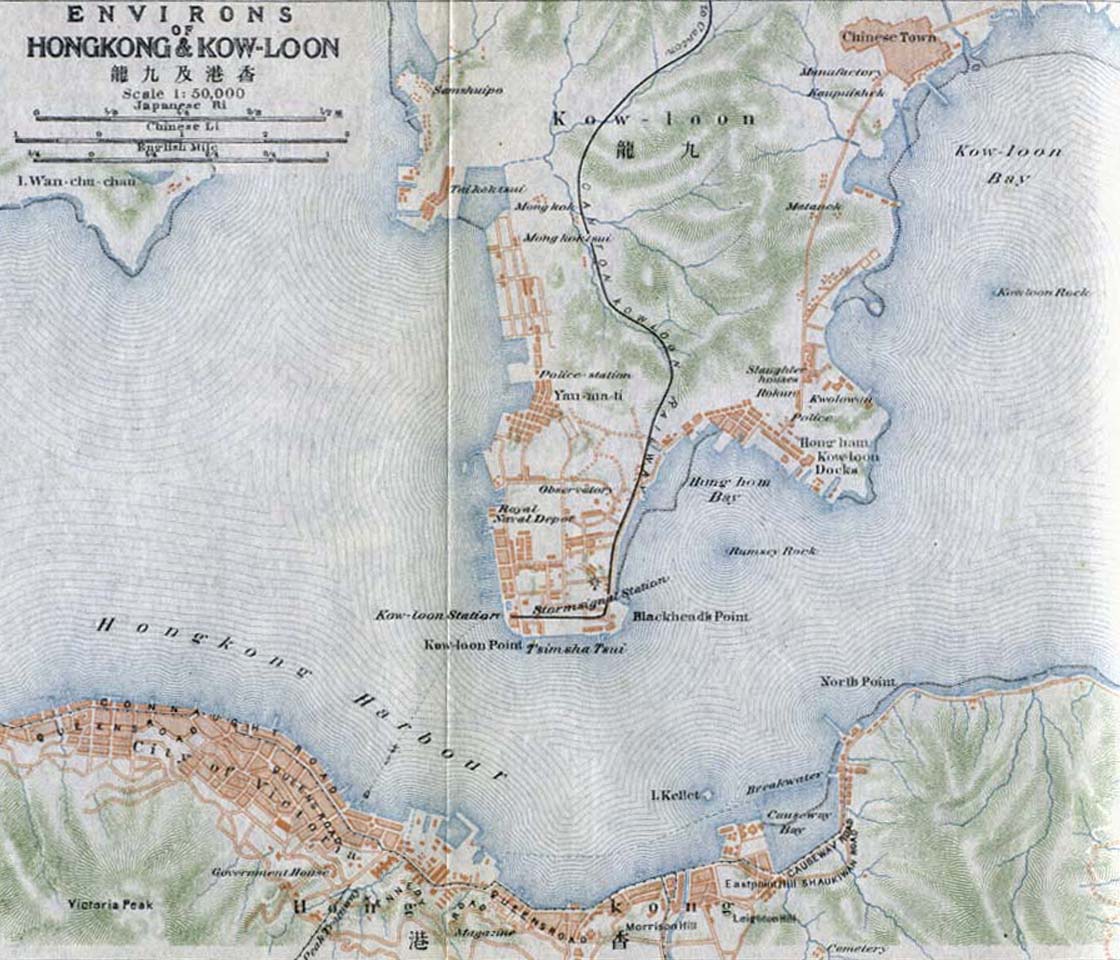

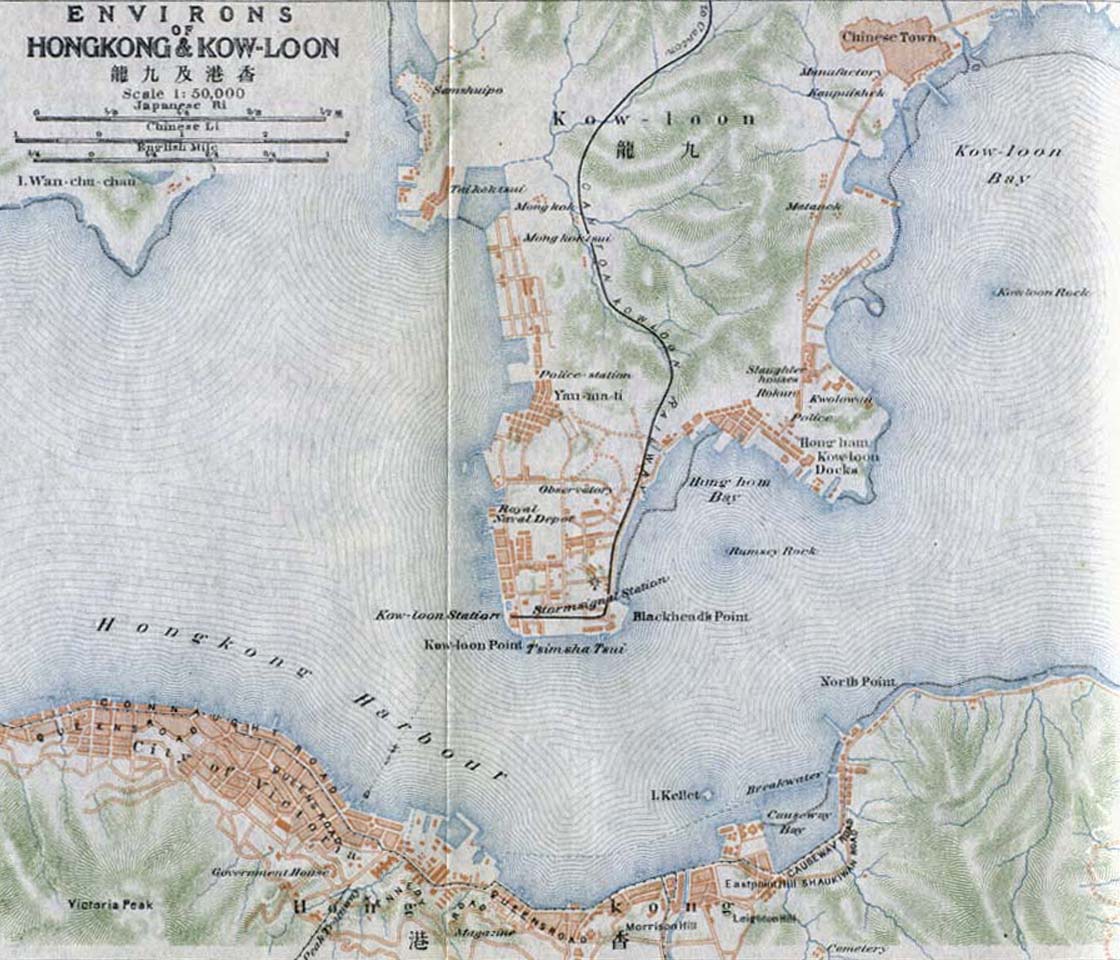

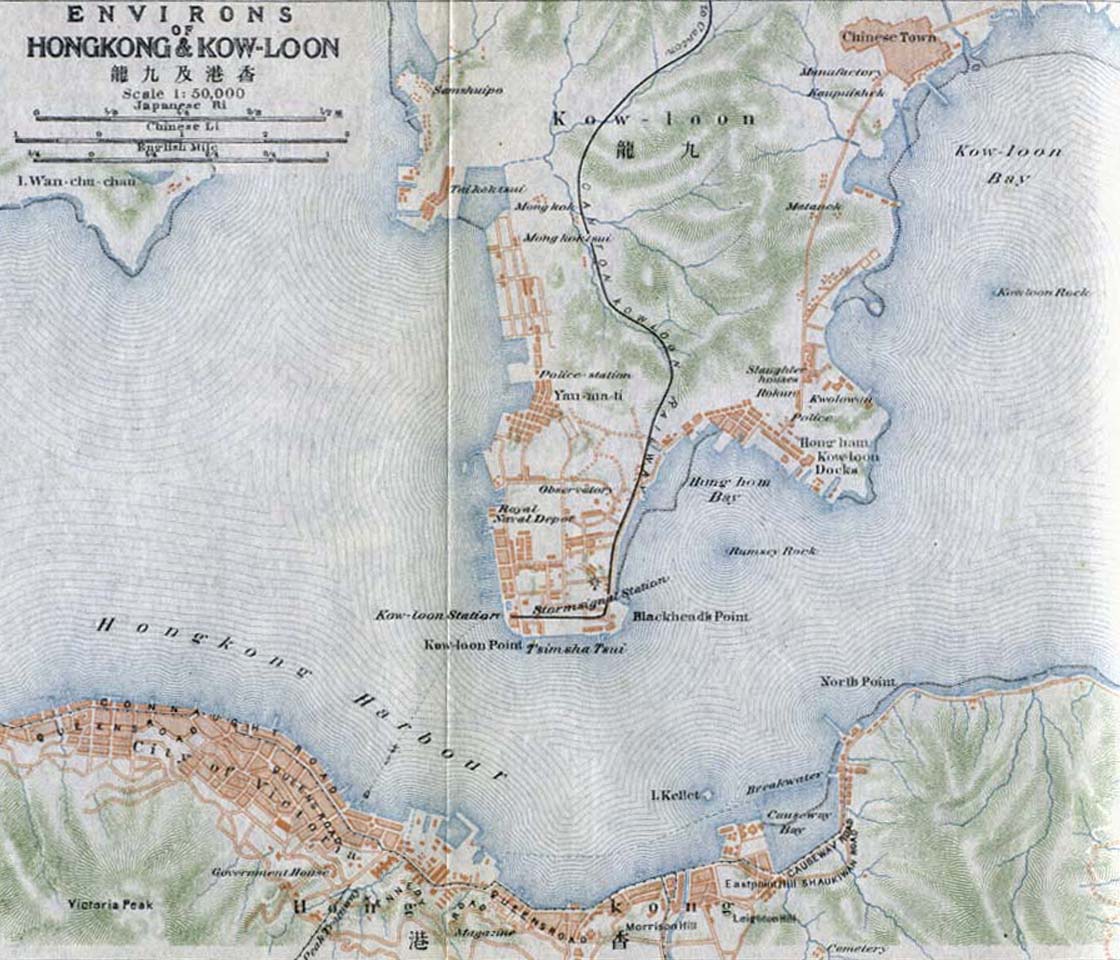

1915 map of the Hong Kong region with the Kowloon Walled City listed as "Chinese Town" at the upper right-hand corner

1915 map of the Hong Kong region with the Kowloon Walled City listed as "Chinese Town" at the upper right-hand corner

Lung Tsun Stone Bridge and Lung Tsun Pavilion (Pavilion for Greeting Officials) of Kowloon Walled City in 1898

The Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory of 1898 handed additional parts of Hong Kong (the New Territories) to Britain for 99 years, but excluded the Walled City, which at the time had a population of roughly 700. China was allowed to continue to keep officials there as long as they did not interfere with the defence of British Hong Kong. The following year, the governor, Sir Henry Blake, suspected that the viceroy of Canton was using troops to aid resistance to the new arrangements. On 14 April 1899, British forces attacked the Walled City, only to find the viceroy's soldiers gone, leaving behind only the mandarin and 150 residents. The Qing dynasty ended its rule in 1912, leaving the Walled City to the British.

Lung Tsun Stone Bridge and Lung Tsun Pavilion (Pavilion for Greeting Officials) of Kowloon Walled City in 1898

The Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory of 1898 handed additional parts of Hong Kong (the New Territories) to Britain for 99 years, but excluded the Walled City, which at the time had a population of roughly 700. China was allowed to continue to keep officials there as long as they did not interfere with the defence of British Hong Kong. The following year, the governor, Sir Henry Blake, suspected that the viceroy of Canton was using troops to aid resistance to the new arrangements. On 14 April 1899, British forces attacked the Walled City, only to find the viceroy's soldiers gone, leaving behind only the mandarin and 150 residents. The Qing dynasty ended its rule in 1912, leaving the Walled City to the British.

Though the British claimed ownership of the Walled City, they did little with it over the following few decades. The protestant church established an old people's home in the old yamen as well as a school and an almshouse in other former offices. Aside from such institutions, however, the Walled City became a mere curiosity for British colonials and tourists to visit; it was labelled as "Chinese Town" on a 1915 map.

In 1933, the Hong Kong authorities announced plans to demolish most of the decaynig Walled City's buildings, compensating the 436 squatters that lived there with new homes. By 1940 only the yamen, the school and one house remained. During the World War II occupation of Hong Kong, the Japanese occupying forces demolished the City's wall and used the stone to expand the nearby Kai Tak Airport.

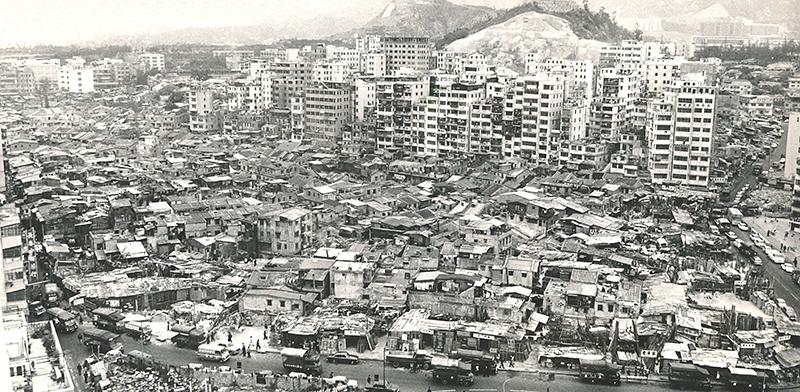

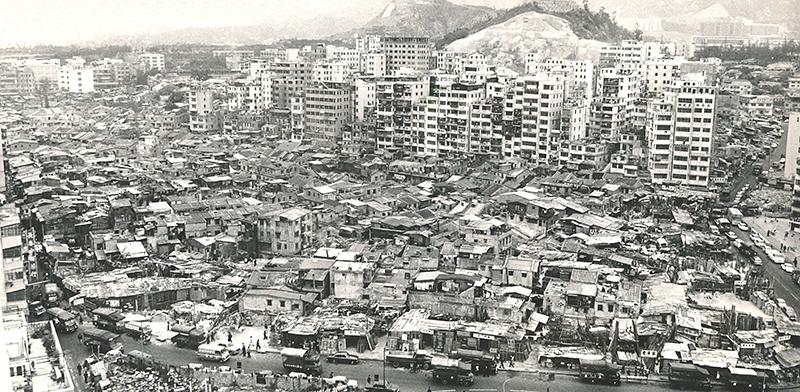

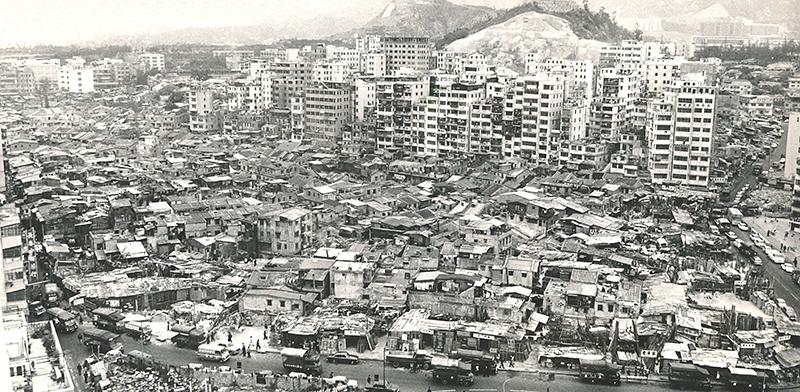

An aerial view of Kowloon Walled City and the neighbouring Sai Tau Tsuen village in 1972

An aerial view of Kowloon Walled City and the neighbouring Sai Tau Tsuen village in 1972

Photo Credit: Ian Lambot

January 1950, a fire broke out that destroyed over 2,500 huts, home to nearly 3,500 families and 17,000 total people. The disaster highlighted the need for proper fire prevention in the largely wooden-built squatter areas, complicated by the lack of political ties with the colonial and Chinese governments. The ruins gave new arrivals to the Walled City the opportunity to build anew, causing speculation that the fire may have been intentionally set.

The south side of the Kowloon Walled City in 1975. The elevation of the buildings begins to reach its maximum height.

The south side of the Kowloon Walled City in 1975. The elevation of the buildings begins to reach its maximum height.

Photo Credit: Ian Lambot

With no government enforcement from the Chinese or the British aside from a few raids by the Royal Hong Kong Police, the Walled City became a haven for crime and drugs. It was only during a 1959 trial for a murder that occurred within the Walled City that the Hong Kong government was ruled to have jurisdiction there. By that time, however, the Walled City was virtually ruled by the triads.

Beginning in the 1950s, triad groups such as the 14K and Sun Yee On gained a stranglehold on the Walled City's numreous brothels, gambling parlors and opium dens. The Walled City had become such a haven for criminals that police would venture into it only in large groups. It was not until 1973 and 1974, when a series of more than 3,500 police raids resulted in over 2,500 arrests and over 1,800 kilograms (4,000 lbs) of seized drugs, that the triads' power began to wane. With public support, particularly from younger residents, the continued raids gradually eroded drug use and violent crime. In 1983, the police commander of Kowloon City District declared the Walled City's crime rate to be under control.

The City also underwent massive construction during the 1960s, with developers building new modular structures above older ones. The city became extremely densely populated, with over 33,000 people in 300 buildings occupying more than 7 acres (2.8 ha). As a result, the City reached its maximum size by the late 1970s and early 1980s; a height restriction of 13 to 14 storeys had been imposed on the city due to the flight path of planes heading toward Kai Ta Airport. As well as limiting building height, the proximity of the airport subjected residents to serious noise pollution for the last 20 years of the city's existence.

Although the rampant crime of earlier decades diminished in later years, the Walled City was still known for its high number of unlicensed doctors and dentists who could operate there without threat of prosecution.

An attempt by the government in 1963 to demolish some shacks in a cornre of the City gave rise to an "anti-demolition committee" that served as the basis for a kaifong association. Charities, religious societies, and other welfare groups were gradually introduced to the City. While medical clinics and schools were unregulated, the Hong Kong government provided some services such as water supply and mail delivery.

Owing to the presence of numerous other green spaces in the area, the Urban Services Department doubted the need for "yet another park" frmo a planning and operations point of view, but the council agreed nonetheless to accept the government's proposal on the condition that the government bear the cost of park construction.

The government distributed some HK$2.7 billion (US$350 million) in compensation to the estimated 33,000 residents and businesses in a plan devised by a special committee of the Hong Kong Housing Authority. Some residents were not satisfied with the compensation and wre forcibly evicted between November 1991 and July 1992. While it was deserted, the empty city was used to film a scene in the 1993 movie "Crime Story".

After four months of planning, demolition of the Walled City began on 23 March 1993 and concluded in April 1994. Construction work on Kowloon Walled City Park started the following month.

Information sourced from Wikipedia.

Information sourced from Wikipedia.

A street at the edge of the City at night in 1993, one year before its demolition.

A street at the edge of the City at night in 1993, one year before its demolition.

Photo Credit: Greg Girard

Kowloon Walled City's early population fluctuated between zero and a few hundred, and began growing steadily shortly after World War II. However, there is no accurate population information available for much of the Walled City's later existence. Official census numbers estimated the Walled City's population at 10,004 in 1971 and 14,617 in 1981, but these figures were commonly considered to be much too low. Informal estimates, on the other hand, often mistakenly included the neighbouring squatter village of Sai Tau Tsuen. Population figures of about 50,000 were also reported.

A thorough government survey in 1987 gave a clearer picture: An estimated 33,000 people resided within the Walled City. Based on this survey, the Walled City had a population density of approximately 1,255,000 inhabitants per suqare kilometer (3,250,000/sq mi) in 1987, making it the most densely populated spot in the world.

The Walled City (城寨; Chéng Zhài; 'Walled City'), as part of Hong Kong Connection's (鏗鏘集; Kēngqiāng jí; 'Resonant Collection') 70th segment, produced by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK), 1979

Hongkongs geheime Stadt – Ein Labyrinth für 50.000 Menschen ("Hong Kong's Secret City: A Labyrinth for 50,000 People"), produced by Österreichischer Rundfunk (ORF), 1989

Kowloon Walled City, as part of Whicker's World, produced by ITV Yorkshire, 1980

City of Imagination: Kowloon Walled City 20 Years Later (archive footage by ORF and Suenn Ho), produced by The Wall Street Journal, 2014

Information sourced from Wikipedia

The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou (last in a succession of five dynasties), ending the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (an era of political upheaval and division in 10th-century Imperial China lasting from 907 to 979).

The Song government was the first in world history to issue banknotes or true paper money nationally and the first Chinese government to establish a permanent standing navy. This dynasty also saw the first known use of gunpowder, as well as the first discernment of true north using a compass.

The Qing dynasty, officially the Great Qing, was the last imperial dynasty of China. It was established in 1636 and ruled from 1644 to 1911. It was preceded by the Ming dynasty and succeeded by the Republic of China.

The Qing multi-cultural empire lasted for almost three centuries and formed the territorial base for modern China. It was the fifth largest empire in world history.

The government initiated unprecedented fiscal and administrative reforms, including elections, a new legal code, and abolition of the examination system.

The Opium Wars were two wars in the mid-19th century involving Great Qing and the British Government and concerned their imposition of trade of opium upon China, thus compromising China's territorial sovereignty and economic power for almost a century.

A triad is one of many branches of Chinese transnational organized crime syndicates based in China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, and in countries with significant Chinese populations.

The Hong Kong triad is distinct from mainland Chinese criminal organizations. In ancient China, the triad was one of three major secret societies. It established branches in Macau, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Chinese communities overseas.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "Triad" is a translation of the Chinese term "San Ho Hui" (or Triple Union Society), referring to the union of heaven, earth and humanity. Another theory posits that the word "triad" was coined by British authorities in colonial Hong Kong as a reference to the triads' use of triangular imagery.

CONTENT WARNING: Some slightly upsetting imagery of animals and drug use.

1915 map of the Hong Kong region with the Kowloon Walled City listed as "Chinese Town" at the upper right-hand corner

Lung Tsun Stone Bridge and Lung Tsun Pavilion (Pavilion for Greeting Officials) of Kowloon Walled City in 1898

An aerial view of Kowloon Walled City and the neighbouring Sai Tau Tsuen village in 1972

Photo Credit: Ian Lambot

The south side of the Kowloon Walled City in 1975. The elevation of the buildings begins to reach its maximum height.

Photo Credit: Ian Lambot

A street at the edge of the City at night in 1993, one year before its demolition.

Photo Credit: Greg Girard

.jpg)

Kawasaki Warehouse, a Japanese game arcade with a Kowloon Walled City theme

Photo Credit: Ken OHYAMA

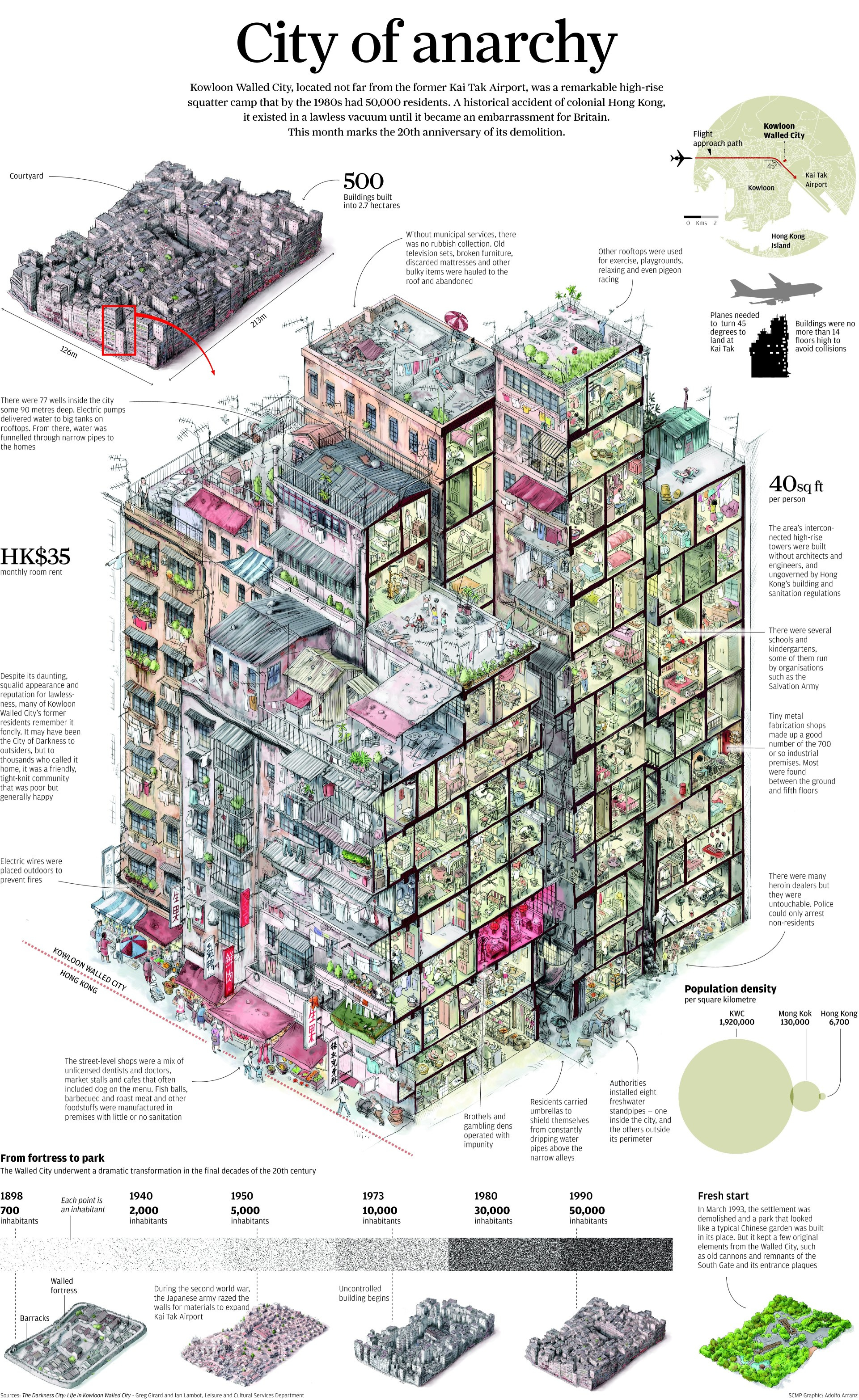

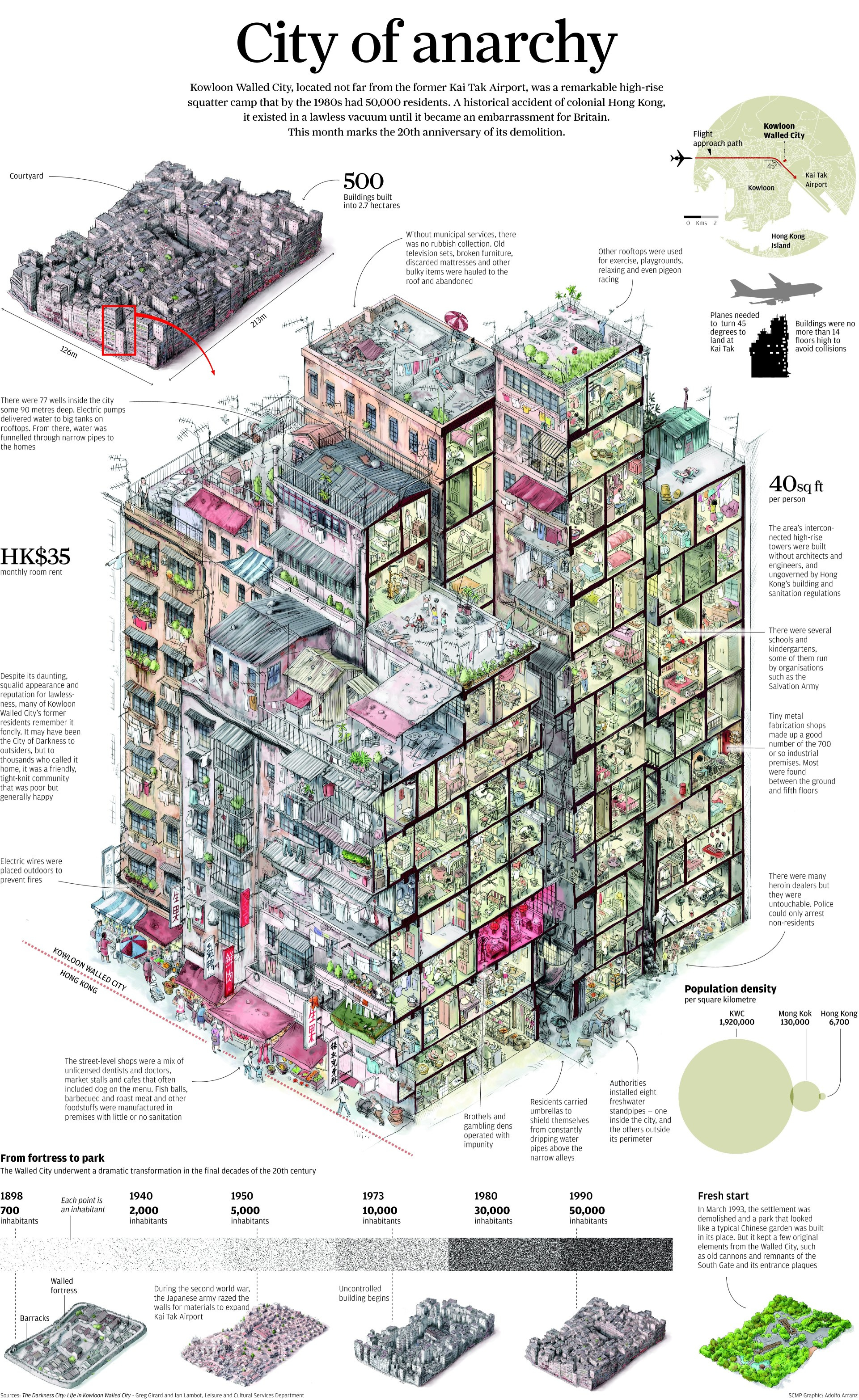

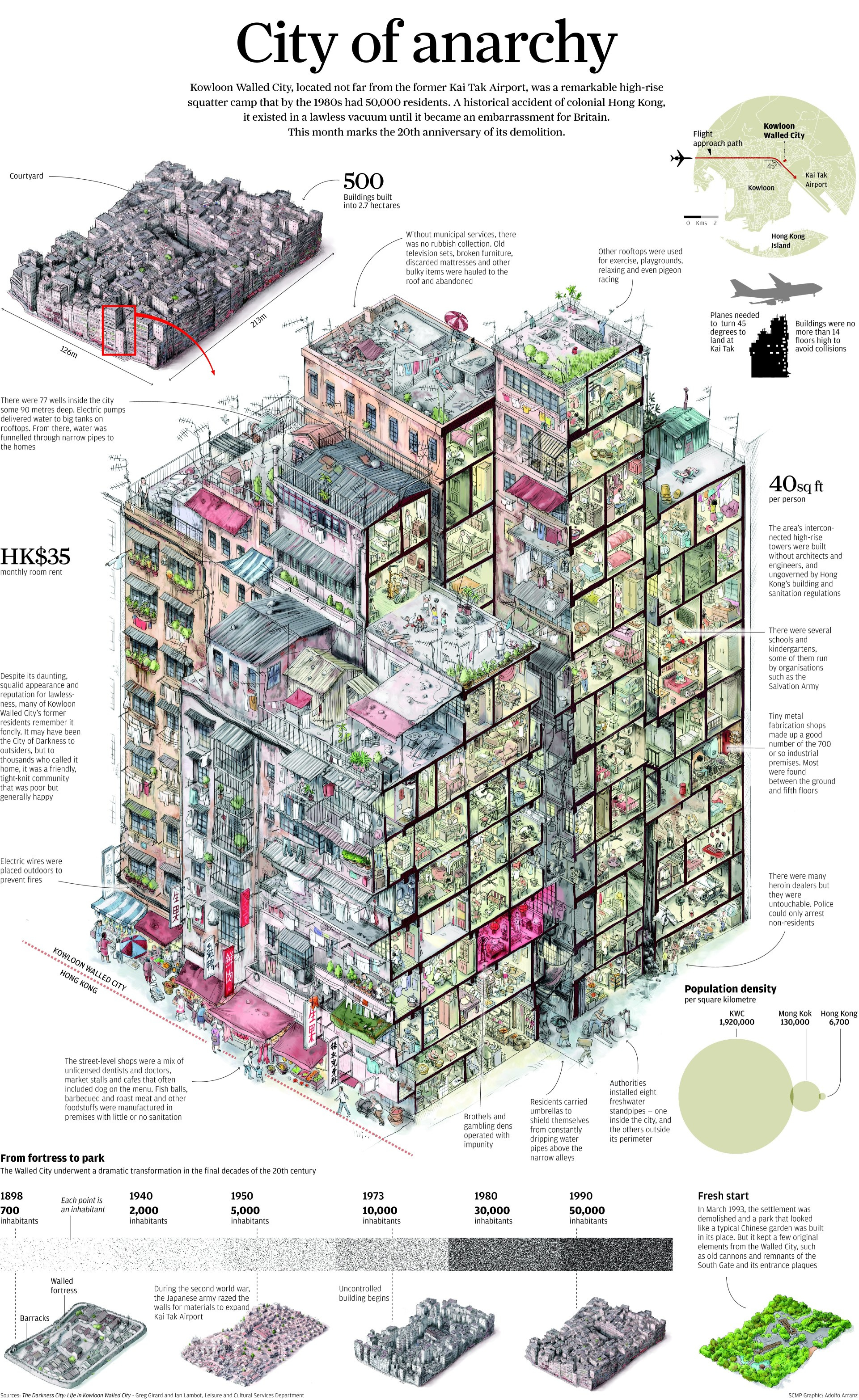

An Infographic detailing facts and figures of life in the Kowloon Walled City by the South China Morning Post.

"Simultaneously communal and anarchic. A contradiction in concrete, within which neighborly compassion coexists side by side with mob brutality. The full gamut of human experience, condensed into the space of a city block. No community quite like it existed before it, and perhaps there will never again be anything like it."

-Alex Beyman, medium.com

Military Outpost

The history of the Walled City can be traced back to the Song Dynasty (960AD-1279), when an outpost was set up to manage the trade of salt. Little took place for hundreds of years afterwards, although 30 guards were stationed there in 1668. A small coastal fort was established around 1810 after Chinese forces abandoned Tung Lung Fort (supposedly a maritime defense fort built on Tung Lung Chau island off the south-east coast of Hong Kong).In 1842, during Qing Emperor Daoguang's reign, Hong Kong Island was ceded to Britain by the Treaty of Nanjing. As a result, the Qing authorities felt it necessary to improve the fort in order to rule the area and check further British influence. The improvements, including the formidable defensive wall, were completed in 1847. The Walled City was captured by rebels during the Taiping Rebellion in 1854 before being retaken a few weeks later. The present Walled City's "Dapeng Association House" forms the remnants of what was previously Lai Enjue's garrison.

1915 map of the Hong Kong region with the Kowloon Walled City listed as "Chinese Town" at the upper right-hand corner

1915 map of the Hong Kong region with the Kowloon Walled City listed as "Chinese Town" at the upper right-hand corner

Lung Tsun Stone Bridge and Lung Tsun Pavilion (Pavilion for Greeting Officials) of Kowloon Walled City in 1898

Lung Tsun Stone Bridge and Lung Tsun Pavilion (Pavilion for Greeting Officials) of Kowloon Walled City in 1898

Though the British claimed ownership of the Walled City, they did little with it over the following few decades. The protestant church established an old people's home in the old yamen as well as a school and an almshouse in other former offices. Aside from such institutions, however, the Walled City became a mere curiosity for British colonials and tourists to visit; it was labelled as "Chinese Town" on a 1915 map.

In 1933, the Hong Kong authorities announced plans to demolish most of the decaynig Walled City's buildings, compensating the 436 squatters that lived there with new homes. By 1940 only the yamen, the school and one house remained. During the World War II occupation of Hong Kong, the Japanese occupying forces demolished the City's wall and used the stone to expand the nearby Kai Tak Airport.

An aerial view of Kowloon Walled City and the neighbouring Sai Tau Tsuen village in 1972

An aerial view of Kowloon Walled City and the neighbouring Sai Tau Tsuen village in 1972Photo Credit: Ian Lambot

Urban Settlement

After Japan's surrender in 1945, China announced its intent to reclaim the Walled City. Refugees fleeing the Chinese Civil War post-1945 poured into Hong Kong, and 2,000 squatters occupied the Walled City by 1947. After a failed attempt to drive them out in 1948, the British adopted a 'hands-off' policy in most matters concerning the Walled City.January 1950, a fire broke out that destroyed over 2,500 huts, home to nearly 3,500 families and 17,000 total people. The disaster highlighted the need for proper fire prevention in the largely wooden-built squatter areas, complicated by the lack of political ties with the colonial and Chinese governments. The ruins gave new arrivals to the Walled City the opportunity to build anew, causing speculation that the fire may have been intentionally set.

The south side of the Kowloon Walled City in 1975. The elevation of the buildings begins to reach its maximum height.

The south side of the Kowloon Walled City in 1975. The elevation of the buildings begins to reach its maximum height.Photo Credit: Ian Lambot

Beginning in the 1950s, triad groups such as the 14K and Sun Yee On gained a stranglehold on the Walled City's numreous brothels, gambling parlors and opium dens. The Walled City had become such a haven for criminals that police would venture into it only in large groups. It was not until 1973 and 1974, when a series of more than 3,500 police raids resulted in over 2,500 arrests and over 1,800 kilograms (4,000 lbs) of seized drugs, that the triads' power began to wane. With public support, particularly from younger residents, the continued raids gradually eroded drug use and violent crime. In 1983, the police commander of Kowloon City District declared the Walled City's crime rate to be under control.

The City also underwent massive construction during the 1960s, with developers building new modular structures above older ones. The city became extremely densely populated, with over 33,000 people in 300 buildings occupying more than 7 acres (2.8 ha). As a result, the City reached its maximum size by the late 1970s and early 1980s; a height restriction of 13 to 14 storeys had been imposed on the city due to the flight path of planes heading toward Kai Ta Airport. As well as limiting building height, the proximity of the airport subjected residents to serious noise pollution for the last 20 years of the city's existence.

Although the rampant crime of earlier decades diminished in later years, the Walled City was still known for its high number of unlicensed doctors and dentists who could operate there without threat of prosecution.

An attempt by the government in 1963 to demolish some shacks in a cornre of the City gave rise to an "anti-demolition committee" that served as the basis for a kaifong association. Charities, religious societies, and other welfare groups were gradually introduced to the City. While medical clinics and schools were unregulated, the Hong Kong government provided some services such as water supply and mail delivery.

Eviction and Demolition

Over time, both the British and the Chinese governments found the City to be increasingly intolerable despite a reduction in the reported crime rate. The quality of life in the city--sanitary conditions in particular--remained far behind the rest of Hong Kong. The Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984 laid the groundwork for the city's demolition. The mutual decision by the two governments to tear down the Walled City was announced on 14 January 1987. On 10 March 1987, following the announcement that the Walled City would be converted to a park, the Secretary for District Administration formally requested the Urban Council agree to take over the site following demolition.Owing to the presence of numerous other green spaces in the area, the Urban Services Department doubted the need for "yet another park" frmo a planning and operations point of view, but the council agreed nonetheless to accept the government's proposal on the condition that the government bear the cost of park construction.

The government distributed some HK$2.7 billion (US$350 million) in compensation to the estimated 33,000 residents and businesses in a plan devised by a special committee of the Hong Kong Housing Authority. Some residents were not satisfied with the compensation and wre forcibly evicted between November 1991 and July 1992. While it was deserted, the empty city was used to film a scene in the 1993 movie "Crime Story".

After four months of planning, demolition of the Walled City began on 23 March 1993 and concluded in April 1994. Construction work on Kowloon Walled City Park started the following month.

Kowloon Walled City Park

Information sourced from Wikipedia.

The area where the Walled City once stood is now Kowloon Walled City Park, adjacent to Carpenter Road Park. The 31,000 m2 (330,000 sq ft) park was completed in August 1995 and handed over to the Urban Council. It was opened officially by Governor Chris Patten a few months later on 22 December. Construction of the park cost a total of HK$76 million.

The park's design is modelled on Jiangnan gardens of the early Qing Dynasty. It is divided into eight landscape features, with the fully restored yamen as its centerpiece. The park's paths and Pavilions are named after streets and buildings in the Walled City. Artifacts from the Walled City, such as five inscribed stones and three old wells, are also on display in the park. The park was designed by the Architectural Services Department, which won a "prestigious award" from the Central Society of Horticulture of Germany for the redevelopment.

Components of the park include:

The Eight Floral Walks, each named after a different plant or flower

The Chess Garden, featuring four 3-by-5-meter (9.8 by 16.4 ft) Chinese chessboards The Garden of Chinese zodiac, containing stone statues of the 12 Chinese zodiac animals

The Garden of Four Seasons (named Guangyin Square after the small open area in the Walled City), a 300 m2 (3,2000 sq ft) garden with plants that symbolise the four seasons

The Six Arts Terrace, a 600 m2 6,500 sq ft) weddnig area containing a garden and the Bamboo Pavilion

The Kuixing Pavilion, including a moon gate framed by two stone tablets and the towering Guibi Rock, which represents Hong Kong's return to China

The Mountain View Pavilion, a two-storey structure resembling a docked boat that provides a good view of the entire park

The Lung Tsun, Yuk Tong, and Lung Nam Pavilions

The yamen and the remains of the South Gate

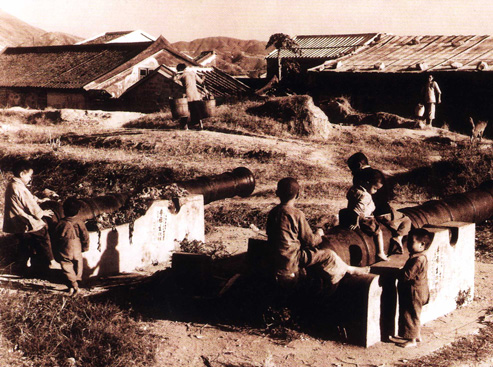

The front of the restored yamen building with one of the original cannons

The front of the restored yamen building with one of the original cannons

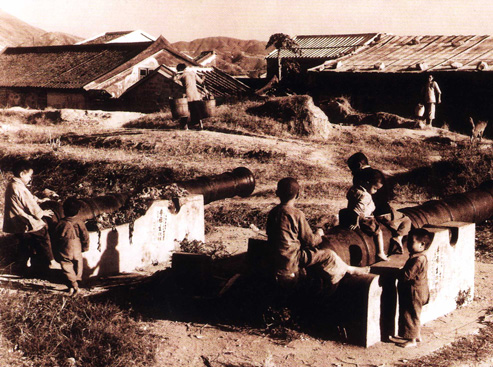

Children of early 20th century Kowloon Walled City residents playing on the yamen cannons

The Antiqueties and Monuments Office conducted archaeological examinations as the Walled City was being demolished, and several cultural remains were discovered. Among them were the Walled City's yamen and remnants of its South Gate, which were officially designated declared monuments of Hong Kong on 4 October 1996.

Children of early 20th century Kowloon Walled City residents playing on the yamen cannons

The Antiqueties and Monuments Office conducted archaeological examinations as the Walled City was being demolished, and several cultural remains were discovered. Among them were the Walled City's yamen and remnants of its South Gate, which were officially designated declared monuments of Hong Kong on 4 October 1996.

The South Gate had originally served as the Walled City's main entrance. Along with its foundation, other remains included two stone plaques inscribed with "South Gate" and "Kowloon Walled City" from the South Gate and a flagstone path that had led up to it. The foundations of the City's wall and East Gate were also discovered. The Hong Kong municipal government preserved the South Gate remnants next to a square in front of the yamen.

The yamen building is made up of three halls. Originally the middle hall served the Assistant Magistrate of Kowloon's administrative office, and the rear block was his residence. After the government officials left the area in 1899, it was used for several other purposes, including an old people's home, a refuge for widows and orphans, a school, and a clinic. It was restored in 1996 and is now found near the center of the park. It contains a photo gallery of the Walled City, and two cannons dating back to 1802 sit at the sides of its entrance.

The park's design is modelled on Jiangnan gardens of the early Qing Dynasty. It is divided into eight landscape features, with the fully restored yamen as its centerpiece. The park's paths and Pavilions are named after streets and buildings in the Walled City. Artifacts from the Walled City, such as five inscribed stones and three old wells, are also on display in the park. The park was designed by the Architectural Services Department, which won a "prestigious award" from the Central Society of Horticulture of Germany for the redevelopment.

Components of the park include:

Declared Monuments

The front of the restored yamen building with one of the original cannons

The front of the restored yamen building with one of the original cannons

Children of early 20th century Kowloon Walled City residents playing on the yamen cannons

Children of early 20th century Kowloon Walled City residents playing on the yamen cannons

The South Gate had originally served as the Walled City's main entrance. Along with its foundation, other remains included two stone plaques inscribed with "South Gate" and "Kowloon Walled City" from the South Gate and a flagstone path that had led up to it. The foundations of the City's wall and East Gate were also discovered. The Hong Kong municipal government preserved the South Gate remnants next to a square in front of the yamen.

The yamen building is made up of three halls. Originally the middle hall served the Assistant Magistrate of Kowloon's administrative office, and the rear block was his residence. After the government officials left the area in 1899, it was used for several other purposes, including an old people's home, a refuge for widows and orphans, a school, and a clinic. It was restored in 1996 and is now found near the center of the park. It contains a photo gallery of the Walled City, and two cannons dating back to 1802 sit at the sides of its entrance.

Architecture

Information sourced from Wikipedia.

The Walled City was located in what became known as the Kowloon City Area of Kowloon. In spite of its transformation from a fort into an urban enclave, the Walled City retained the same basic alyout. The original fort was built on a slope and consisted of a 2.6-hectare (0.010 sq mi) plot measuring about 210 by 120 meters (690 by 390 ft). The stone wall surrounding it had four entrances and measured 4 meters (13 ft) tall and 4.6 meters (15 ft) thick before it was dismantled in 1943.

Construction surged dramatically during the 1960s and 1970s, until the formerly low-rise City consisted almost entirely of buildings with 10 storeys or more (with the notable exception of the yamen in its center).

However, due to the Kai Tak Airport's position 800 meters (0.50 mi) south of the City, buildings did not exceed 14 storeys. The two-storey Sai Tau Tsuen settlement bordered the Walled City to the south and west until it was cleared in 1985 and replaced with Carpenter Road Park.

The City's dozens of alleyways were often only 1-2 m (3.3-6.6 ft) wide, and had poor lighting and drainage. An informal network of staircases and passageways also formed on upper levels, which was so extensive that one could travel north-to-south through the entire City without ever touching solid ground. Construction in the City went unregulated, and most of the roughly 350 buildings were built with poor foundations and few or no utilities. Because apartments were so small--a typical unit was 23 m2 (250 sq ft)--space was maximised with wider upper floors, caged balconies and rooftop additions. Roofs in the City were full of televiison antennae, clotheslines, water tanks and garbage, and could be crossed using a series of ladders.

Construction surged dramatically during the 1960s and 1970s, until the formerly low-rise City consisted almost entirely of buildings with 10 storeys or more (with the notable exception of the yamen in its center).

However, due to the Kai Tak Airport's position 800 meters (0.50 mi) south of the City, buildings did not exceed 14 storeys. The two-storey Sai Tau Tsuen settlement bordered the Walled City to the south and west until it was cleared in 1985 and replaced with Carpenter Road Park.

The City's dozens of alleyways were often only 1-2 m (3.3-6.6 ft) wide, and had poor lighting and drainage. An informal network of staircases and passageways also formed on upper levels, which was so extensive that one could travel north-to-south through the entire City without ever touching solid ground. Construction in the City went unregulated, and most of the roughly 350 buildings were built with poor foundations and few or no utilities. Because apartments were so small--a typical unit was 23 m2 (250 sq ft)--space was maximised with wider upper floors, caged balconies and rooftop additions. Roofs in the City were full of televiison antennae, clotheslines, water tanks and garbage, and could be crossed using a series of ladders.

Population

A street at the edge of the City at night in 1993, one year before its demolition.

A street at the edge of the City at night in 1993, one year before its demolition.Photo Credit: Greg Girard

A thorough government survey in 1987 gave a clearer picture: An estimated 33,000 people resided within the Walled City. Based on this survey, the Walled City had a population density of approximately 1,255,000 inhabitants per suqare kilometer (3,250,000/sq mi) in 1987, making it the most densely populated spot in the world.

Culture

Unlike the rest of Hong Kong, there were no electricity or sewage systems, and water supply was supposedly limited to an inconsistently-reported number of taps where a queue of people stood constantly waiting for water. Lining up for water was such a time-consuming chore that it became one of the City's paid jobs. The water supply itself was set up by the residents themselves, working together to dig wells and build thousands of pipes that wound through the buildings, taking turns conserving power so that water could be shared successfully.

Electricity would be tapped from the street lights outside of the City, transferred via a complex and dangerous network of cables. This, combined with the presence of several layers of built-up garbage, meant that fires were common occurrences.

The lower levels were shrouded in permanent darkness, so many of the alleys were lit by fluorescent lights that were always on. Citizens would carry umbrellas in these alleyways as the intricate network of overhead pipes spreading throughout the City was almost constantly leaking dirty water.

In response to the difficult living conditions, residents of the Walled City formed a tightly-knit community. Despite its seedy reputation, the Walled City offered a sense of togetherness to thousands of people.

Within families, wives often did housekeeping, while grandmothers cared for their grandchildren and other children from surrounding households.

Multiple generations of families grew up here, and called Kowloon Walled City their home.

The city's community established groups and services, including unregulated hospitals, schools and clinics, some of them run by organisations such as the Salvation Army. Trades and small businesses also operated within the City's walls, all free to ignore health, fire and labor codes. This drew in hordes of working-class citizens, coming to the City just to be able to receive affordable healthcare and services, regardless of the quality thereof.

To make the most of the cramped conditions, these establishments shared space with one another, with schools and salons being converted into strip clubs and gambling halls at night.

The street-level shops were a mix of unlicensed dentists, doctors, market stalls and cafés that often included dog on the menu. Fish balls, barbecued/roast meat and other foodstuffs were manufactured in premises with little to no sanitation. Tiny metal fabrication shops made up a good number of the 700 or so industrial premises, with most of these being found between the ground and fifth floors.

Fish balls were some of the most common products manufactured in the City, which Kowloon producers sold to local restaurants.

Anecdotes about the City suggest that 8 out of 10 fish balls eaten in Hong Kong during the '60s were made in the Walled City.

The City's rooftops were an important gathering place, especially for residents who lived on the upper floors. Parents used them to relax, and children would play or do homework there after school. They were a sanctuary for the residents of the Walled City, with the rooftops being the only escape from the claustrophobia of the City below.

They also hosted pigeon races here, which residents gambled on like horse races.

The rooftops were also dangerous, however - there were small gaps between the buildings, and the lack of organized garbage collection left the rooftops becoming cluttered with discarded furniture and appliances.

The yamen in the heart of the City was also a major social center, a place for residents to talk, have tea or watch television, and to take classes such as calligraphy. The Old People's Centre also held religious meetings for Christians and others. Other religious institutions included the Fuk Tak and Tin Hau temples, which were used for a combination of Buddhist, Taoist and Animist practices.

An Infographic detailing facts and figures of life in the Kowloon Walled City by the South China Morning Post.

An Infographic detailing facts and figures of life in the Kowloon Walled City by the South China Morning Post.

The triads also supposedly worked with the City's residents, acting as a kind of "city council" (albeit one funded by drugs and enforced through violence) as they settled disputes between businesses, organized a garbage disposal system and created a volunteer fire department.

Many drug dealers operated in the Walled City with impunity, completely untouchable as the Police could only arrest non-residents.

As a result, drug addiction was naturally a major problem in the Walled City. Many became dependent on heroin, often dying when they could no longer afford to feed their habits. Family members of these addicts would reportedly simply move their bodies into the restrooms and leave them there.

In the 1970s, anti-corruption campaigns saw the law being enforced more heavily even in the Walled City. The crime rate subsided, and the triads lost their presence. Community activists started demanding more for the City and its residents. Government services, such as mail and water, were eventually introduced, but ongoing sanitation problems and issues from decades of unregulated building persisted until the end of the City's existence.

When the Kowloon Walled City was torn down, many of its residents were dissatisfied with their eviction and the financial compensation they received. Many, years on, even when fully resettled into the rest of Hong Kong, looked back to their days in the Walled City as a “happier time.”

“You don’t want to romanticize a slum, you know. Because it was that. But it was much more than that. The Walled City was a kind of architectural touchstone in terms of what a city can be — unplanned, self-generated, unregulated.”

- Greg Girard, Photographer & Chronicler of Life in Kowloon

Electricity would be tapped from the street lights outside of the City, transferred via a complex and dangerous network of cables. This, combined with the presence of several layers of built-up garbage, meant that fires were common occurrences.

The lower levels were shrouded in permanent darkness, so many of the alleys were lit by fluorescent lights that were always on. Citizens would carry umbrellas in these alleyways as the intricate network of overhead pipes spreading throughout the City was almost constantly leaking dirty water.

In response to the difficult living conditions, residents of the Walled City formed a tightly-knit community. Despite its seedy reputation, the Walled City offered a sense of togetherness to thousands of people.

Within families, wives often did housekeeping, while grandmothers cared for their grandchildren and other children from surrounding households.

Multiple generations of families grew up here, and called Kowloon Walled City their home.

The city's community established groups and services, including unregulated hospitals, schools and clinics, some of them run by organisations such as the Salvation Army. Trades and small businesses also operated within the City's walls, all free to ignore health, fire and labor codes. This drew in hordes of working-class citizens, coming to the City just to be able to receive affordable healthcare and services, regardless of the quality thereof.

To make the most of the cramped conditions, these establishments shared space with one another, with schools and salons being converted into strip clubs and gambling halls at night.

The street-level shops were a mix of unlicensed dentists, doctors, market stalls and cafés that often included dog on the menu. Fish balls, barbecued/roast meat and other foodstuffs were manufactured in premises with little to no sanitation. Tiny metal fabrication shops made up a good number of the 700 or so industrial premises, with most of these being found between the ground and fifth floors.

Fish balls were some of the most common products manufactured in the City, which Kowloon producers sold to local restaurants.

Anecdotes about the City suggest that 8 out of 10 fish balls eaten in Hong Kong during the '60s were made in the Walled City.

The City's rooftops were an important gathering place, especially for residents who lived on the upper floors. Parents used them to relax, and children would play or do homework there after school. They were a sanctuary for the residents of the Walled City, with the rooftops being the only escape from the claustrophobia of the City below.

They also hosted pigeon races here, which residents gambled on like horse races.

The rooftops were also dangerous, however - there were small gaps between the buildings, and the lack of organized garbage collection left the rooftops becoming cluttered with discarded furniture and appliances.

The yamen in the heart of the City was also a major social center, a place for residents to talk, have tea or watch television, and to take classes such as calligraphy. The Old People's Centre also held religious meetings for Christians and others. Other religious institutions included the Fuk Tak and Tin Hau temples, which were used for a combination of Buddhist, Taoist and Animist practices.

An Infographic detailing facts and figures of life in the Kowloon Walled City by the South China Morning Post.

An Infographic detailing facts and figures of life in the Kowloon Walled City by the South China Morning Post.Many drug dealers operated in the Walled City with impunity, completely untouchable as the Police could only arrest non-residents.

As a result, drug addiction was naturally a major problem in the Walled City. Many became dependent on heroin, often dying when they could no longer afford to feed their habits. Family members of these addicts would reportedly simply move their bodies into the restrooms and leave them there.

In the 1970s, anti-corruption campaigns saw the law being enforced more heavily even in the Walled City. The crime rate subsided, and the triads lost their presence. Community activists started demanding more for the City and its residents. Government services, such as mail and water, were eventually introduced, but ongoing sanitation problems and issues from decades of unregulated building persisted until the end of the City's existence.

When the Kowloon Walled City was torn down, many of its residents were dissatisfied with their eviction and the financial compensation they received. Many, years on, even when fully resettled into the rest of Hong Kong, looked back to their days in the Walled City as a “happier time.”

“You don’t want to romanticize a slum, you know. Because it was that. But it was much more than that. The Walled City was a kind of architectural touchstone in terms of what a city can be — unplanned, self-generated, unregulated.”

- Greg Girard, Photographer & Chronicler of Life in Kowloon

Legacy

Memoirs and autobiographies

A few of the people who spent time in Kowloon Walled City have written accounts of their experiences. Evangelist Jackie Pullinger wrote a 1989 memoir, Crack in the Wall, about her involvement in treating drug addicts within the Walled City. In his 2004 autobiography Gweilo, Martin Booth describes his exploration of the Walled City as a child in the 1950s.Works specifically documenting the Walled City

Books and research papersCity of Darkness: Life in Kowloon Walled City, by Ian Lambot (writer, photographer) and Greg Girard (photographer), published by Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn, 1993, ISBN 9783433023556 and Watermark, 1999, ISBN 9781873200131

City of Darkness: Revisited, by Ian Lambot (writer, photographer) and Greg Girard (photographer), published by Watermark, 2014, ISBN 9781873200889 (revised edition of City of Darkness)

Kyūryūjō Tanbō Makutsu de Kurasu Hitobito: City of Darkness (九龍城探訪 魔窟で暮らす人々 -City of Darkness-, "Kowloon Walled City Exploration: People Who Live in the Devil's Den (City of Darkness)"), by Ian Lambot (writer, photographer) and Greg Girard (photographer), published by EastPress, 2004, ISBN 9784872574234 (Japanese edition of City of Darkness)

Daizukai Kyūryūjō (大図解九龍城, "Grand Kowloon Walled City Schematics"), by the Kyūryūjō Tankentai (the "Kowloon Walled City Exploration Team"), including Hitomi Terasawa (illustrator), Takayuki Suzuki (architect) and Hiroaki Kani (supervisor), published by Iwanami Shoten, 1997, ISBN 9784000080705

Kyūryūjōsai (九龍城砦, "Kowloon Walled City"), by Ryūji Miyamoto (photographer), Hiroshi Aramata (text contributor) and Ken'ichi Ōhashi (text contributor), published by Heibonsha, 1997, ISBN 9784582277364; Heibonsha, 1998, ISBN 9784582277364; Heibonsha, 1999, ISBN 9784582277364

Saigo no Kyūryūjōsai (最期の九龍城砦, "The End of Kowloon Walled City"), by Shintarō Nakamura, published by Shinpusha, 1996, ISBN 9784883066469

An Architectural Study on the Kowloon Walled City: Preliminary Findings, by Suenn Ho, published by Columbia University, 1992

Jiulong Cheng Zhai shihua (九龍城寨史話; 'Kowloon Walled City's History'), by Lu Jinzhe, published by Joint Publishing, 1997, ISBN 9789620406829

Jiulong Cheng Zhai: Yige teshu shequ di dili toushi (九龍城寨:一個特殊社區的地理透視; 'Kowloon Walled City: A Geographical Perspective of a Special Community'), by Huang Junyao et al., published by the Chinese University of Hong Kong – Department of Geography, 1992

FARMAX: Excursions on Density, by Winy Maas, Jacob van Rijs and Richard Koek (main contributors), published by 010 Publishers, 1998, ISBN 9789064502668; 010 Publishers, 2006, ISBN 9789064505874

Documentary filmsCity of Darkness: Revisited, by Ian Lambot (writer, photographer) and Greg Girard (photographer), published by Watermark, 2014, ISBN 9781873200889 (revised edition of City of Darkness)

Kyūryūjō Tanbō Makutsu de Kurasu Hitobito: City of Darkness (九龍城探訪 魔窟で暮らす人々 -City of Darkness-, "Kowloon Walled City Exploration: People Who Live in the Devil's Den (City of Darkness)"), by Ian Lambot (writer, photographer) and Greg Girard (photographer), published by EastPress, 2004, ISBN 9784872574234 (Japanese edition of City of Darkness)

Daizukai Kyūryūjō (大図解九龍城, "Grand Kowloon Walled City Schematics"), by the Kyūryūjō Tankentai (the "Kowloon Walled City Exploration Team"), including Hitomi Terasawa (illustrator), Takayuki Suzuki (architect) and Hiroaki Kani (supervisor), published by Iwanami Shoten, 1997, ISBN 9784000080705

Kyūryūjōsai (九龍城砦, "Kowloon Walled City"), by Ryūji Miyamoto (photographer), Hiroshi Aramata (text contributor) and Ken'ichi Ōhashi (text contributor), published by Heibonsha, 1997, ISBN 9784582277364; Heibonsha, 1998, ISBN 9784582277364; Heibonsha, 1999, ISBN 9784582277364

Saigo no Kyūryūjōsai (最期の九龍城砦, "The End of Kowloon Walled City"), by Shintarō Nakamura, published by Shinpusha, 1996, ISBN 9784883066469

An Architectural Study on the Kowloon Walled City: Preliminary Findings, by Suenn Ho, published by Columbia University, 1992

Jiulong Cheng Zhai shihua (九龍城寨史話; 'Kowloon Walled City's History'), by Lu Jinzhe, published by Joint Publishing, 1997, ISBN 9789620406829

Jiulong Cheng Zhai: Yige teshu shequ di dili toushi (九龍城寨:一個特殊社區的地理透視; 'Kowloon Walled City: A Geographical Perspective of a Special Community'), by Huang Junyao et al., published by the Chinese University of Hong Kong – Department of Geography, 1992

FARMAX: Excursions on Density, by Winy Maas, Jacob van Rijs and Richard Koek (main contributors), published by 010 Publishers, 1998, ISBN 9789064502668; 010 Publishers, 2006, ISBN 9789064505874

The Walled City (城寨; Chéng Zhài; 'Walled City'), as part of Hong Kong Connection's (鏗鏘集; Kēngqiāng jí; 'Resonant Collection') 70th segment, produced by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK), 1979

Hongkongs geheime Stadt – Ein Labyrinth für 50.000 Menschen ("Hong Kong's Secret City: A Labyrinth for 50,000 People"), produced by Österreichischer Rundfunk (ORF), 1989

Kowloon Walled City, as part of Whicker's World, produced by ITV Yorkshire, 1980

City of Imagination: Kowloon Walled City 20 Years Later (archive footage by ORF and Suenn Ho), produced by The Wall Street Journal, 2014

Appearances in Media

Information sourced from Wikipedia

Many authors, filmmakers, game designers and visual artists have used the Walled City to convey a sense of oppressive urbanisation or unfettered criminality. In literature, Robert Ludlum's novel "The Bourne Supremacy" uses the Walled City as one of its settings. The City appears as a virtual reality environment (described by Steven Poole as an "oasis of political and creative freedom") in William Gibson's "Bridge trilogy", and as a contrast with Singapore in his Wired article "Disneyland with the Death Penalty". In the manga "Crying Freeman", the titular character's wife travels to the Walled City to master her swordsmanship and control a cursed sword. The manga "Blood+: Kowloon Nights" uses the Walled Citty as the setting for a series of murders. The Walled City finds an extensive mention in Doctor Robin Cook's 1991 novel "Vital Signs". The filth, squalor an dthe crime-oriented nature of the area is described vividly when the characters Marissa and Tristan Williams pass by the back-lanes. The later part of Episode 3 and Episode 4 of the anime "Street Fighter II V" are set in the Kowloon Walled City, depicted as a dark and lawless area where Ryu, Ken and Chun-Li have to fight for their lives at every turn, being rescued by the police once they reach the Walled City's limits.

In the collaborative fiction website "The SCP Foundation" there is an article named "SCP-184", describing an object also known as "The Architect", with the power to make buildings grow in size and complexity in the inside without altering the outside of the building. The article narrates the search for the object as it is hidden by inhabitants in Kowloon Walled City.

The 1982 Shaw Brothers film "Brothers from the Walled City" is set in Kowloon Walled City. The 1984 gangster film "Long Arm of the Law" features the Walled City as a refuge for gang members before they are gunned down by police. In the 1988 film "Bloodsport", starring Jean-Claude Van Damme, the Walled City is the setting for a martial arts tournament. The 1992 non-narrative film "Baraka" features several highly detailed shots of the Walled City shortly before its demolition. The 1993 film "Crime Story" starring Jackie Chan was partly filmed in the deserted Walled City, and includes real scenes of building explosions. A walled neighborhood called the Narrows in the 2005 film " Batman Begins" was inspired by the Walled City. The 2006 Hong Kong horror film "Re-cycle" features a decrepit, nightmarish version of the Walled City, complete with tortured souls from which the protagonist must flee. The 2016 TVB martial arts drama "A Fist Within Four Walls" takes place in the triad-ridden Walled City in the early 1960s.

Kowloon Walled City is depicted in several games, including "Kowloon's Gate" and "Shenmue II". The game "Stranglehold", a sequel to the film "Hard Boiled", features a version of the Walled City filled with hundreds of triad members. In the games "Fear Effect" and "Fear Effect 2", photographs of the Walled City were used as inspiration for "moods, camera angles and lighting". Concept art for the MMORPG "Guild Wars: Factions" depicts massive, densely packed structures inspired by the Walled City. The pen-and-paper RPG "Shadowrun" and CRPG "Shadowrun: Hong Kong" include a crime-ridden, rebuilt version of the Walled City set in 2056. The Walled City also features in a level of the single player campaign for the 2010 game "Call of Duty: Black Ops". Kowloon later appeared as a multiplayer map for the game in a 2011 Map Pack expansion.

A partial recreation of the Kowloon Walled City exists in the Anata No Warehouse, an amusement arcade that opened in 2009 in the Japanese suburb of Kawasaki, Kanagawa. The designer's desire to accurately replicate the atmosphere of the Walled City is reflected in the arcade's narrow corridors, electrical wires, pipes, postboxes, signboards, neon lights, frayed posters and various other small touches that provide an air of authenticity.

In the collaborative fiction website "The SCP Foundation" there is an article named "SCP-184", describing an object also known as "The Architect", with the power to make buildings grow in size and complexity in the inside without altering the outside of the building. The article narrates the search for the object as it is hidden by inhabitants in Kowloon Walled City.

The 1982 Shaw Brothers film "Brothers from the Walled City" is set in Kowloon Walled City. The 1984 gangster film "Long Arm of the Law" features the Walled City as a refuge for gang members before they are gunned down by police. In the 1988 film "Bloodsport", starring Jean-Claude Van Damme, the Walled City is the setting for a martial arts tournament. The 1992 non-narrative film "Baraka" features several highly detailed shots of the Walled City shortly before its demolition. The 1993 film "Crime Story" starring Jackie Chan was partly filmed in the deserted Walled City, and includes real scenes of building explosions. A walled neighborhood called the Narrows in the 2005 film " Batman Begins" was inspired by the Walled City. The 2006 Hong Kong horror film "Re-cycle" features a decrepit, nightmarish version of the Walled City, complete with tortured souls from which the protagonist must flee. The 2016 TVB martial arts drama "A Fist Within Four Walls" takes place in the triad-ridden Walled City in the early 1960s.

Kowloon Walled City is depicted in several games, including "Kowloon's Gate" and "Shenmue II". The game "Stranglehold", a sequel to the film "Hard Boiled", features a version of the Walled City filled with hundreds of triad members. In the games "Fear Effect" and "Fear Effect 2", photographs of the Walled City were used as inspiration for "moods, camera angles and lighting". Concept art for the MMORPG "Guild Wars: Factions" depicts massive, densely packed structures inspired by the Walled City. The pen-and-paper RPG "Shadowrun" and CRPG "Shadowrun: Hong Kong" include a crime-ridden, rebuilt version of the Walled City set in 2056. The Walled City also features in a level of the single player campaign for the 2010 game "Call of Duty: Black Ops". Kowloon later appeared as a multiplayer map for the game in a 2011 Map Pack expansion.

A partial recreation of the Kowloon Walled City exists in the Anata No Warehouse, an amusement arcade that opened in 2009 in the Japanese suburb of Kawasaki, Kanagawa. The designer's desire to accurately replicate the atmosphere of the Walled City is reflected in the arcade's narrow corridors, electrical wires, pipes, postboxes, signboards, neon lights, frayed posters and various other small touches that provide an air of authenticity.

Glossary

Yamen Building

A yamen was the administrative office or residence of a local bureaucrat or mandarin (bureaucrat scholar) in imperial China. A yamen can also be any governmental office or body headed by a mandarin, at any level of govrenment. The term has been widely used in China for centuries, but appeared in English during the Qing dynasty.Song Dynasty

The Song dynasty was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279.The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou (last in a succession of five dynasties), ending the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (an era of political upheaval and division in 10th-century Imperial China lasting from 907 to 979).

The Song government was the first in world history to issue banknotes or true paper money nationally and the first Chinese government to establish a permanent standing navy. This dynasty also saw the first known use of gunpowder, as well as the first discernment of true north using a compass.

Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty, officially the Great Qing, was the last imperial dynasty of China. It was established in 1636 and ruled from 1644 to 1911. It was preceded by the Ming dynasty and succeeded by the Republic of China.

The Qing multi-cultural empire lasted for almost three centuries and formed the territorial base for modern China. It was the fifth largest empire in world history.

The government initiated unprecedented fiscal and administrative reforms, including elections, a new legal code, and abolition of the examination system.

Opium Wars

The Opium Wars were two wars in the mid-19th century involving Great Qing and the British Government and concerned their imposition of trade of opium upon China, thus compromising China's territorial sovereignty and economic power for almost a century.

Triads

A triad is one of many branches of Chinese transnational organized crime syndicates based in China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, and in countries with significant Chinese populations.

The Hong Kong triad is distinct from mainland Chinese criminal organizations. In ancient China, the triad was one of three major secret societies. It established branches in Macau, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Chinese communities overseas.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "Triad" is a translation of the Chinese term "San Ho Hui" (or Triple Union Society), referring to the union of heaven, earth and humanity. Another theory posits that the word "triad" was coined by British authorities in colonial Hong Kong as a reference to the triads' use of triangular imagery.

Videos

City of Imagination: Kowloon Walled City 20 Years Later

Wall Street JournalCONTENT WARNING: Some slightly upsetting imagery of animals and drug use.

A rare look inside the Kowloon Walled City in 1990

South China Morning PostGallery

1915 map of the Hong Kong region with the Kowloon Walled City listed as "Chinese Town" at the upper right-hand corner

Lung Tsun Stone Bridge and Lung Tsun Pavilion (Pavilion for Greeting Officials) of Kowloon Walled City in 1898

An aerial view of Kowloon Walled City and the neighbouring Sai Tau Tsuen village in 1972

Photo Credit: Ian Lambot

The south side of the Kowloon Walled City in 1975. The elevation of the buildings begins to reach its maximum height.

Photo Credit: Ian Lambot

A street at the edge of the City at night in 1993, one year before its demolition.

Photo Credit: Greg Girard

Kawasaki Warehouse, a Japanese game arcade with a Kowloon Walled City theme

Photo Credit: Ken OHYAMA

An Infographic detailing facts and figures of life in the Kowloon Walled City by the South China Morning Post.

"Simultaneously communal and anarchic. A contradiction in concrete, within which neighborly compassion coexists side by side with mob brutality. The full gamut of human experience, condensed into the space of a city block. No community quite like it existed before it, and perhaps there will never again be anything like it."

-Alex Beyman, medium.com

.jpg)